Activity 1: Narrate the Chapter

- After you listen to the chapter, narrate the chapter aloud using your own words.

Activity 2: Illustrate How People Organize

Draw the process of how people organize into groups.

- Click the crayon above. Complete page 23 of 'Second Grade World History Coloring Pages, Copywork, and Writing.'

- Draw a family, the ancient unit of organization. Label the drawing, 'FAMILY UNIT.'

- Draw a clan, a group of families, the temporary ancient unit that pulled families together in times of trouble. Label the drawing, 'CLAN UNIT.'

- Draw a village, a more permanent group of families than clans. Label the drawing, 'VILLAGE UNIT.'

- Draw a state, a grouping of many villages or cities, the current predominant unit of organization. Label the drawing, 'STATE UNIT.'

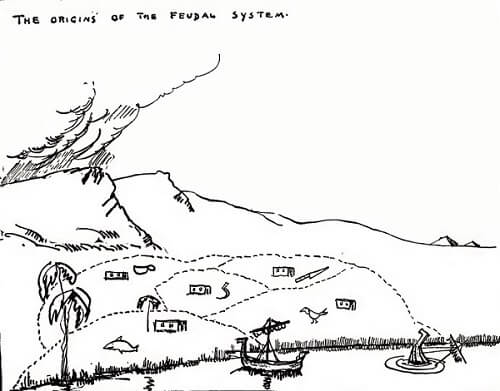

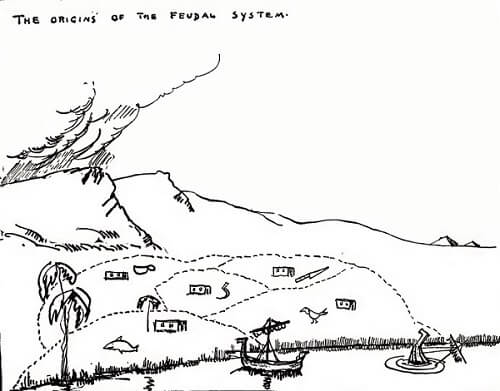

Activity 3: Can You Find It?

Find the following in the picture:

- Individual Farms

- Houses

- Family Symbols (Hieroglyphics)

- Mr. Fish's Farm

- Mr. Sparrow's Farm

- Mr. Cup's Farm

- Mr. Knife's Farm

- Mr. Sickle's Farm

- Palm Trees

- Mr. Sparrow's Boat

- Mr. Fish's Boat

- The Nile River

- The Pyramids

Activity 4: Complete Coloring Pages, Copywork, and Writing

- Click the crayon above. Complete pages 24-25 of 'Second Grade World History Coloring Pages, Copywork, and Writing.'

Ancient Man

Ancient Man

Ancient Man

Ancient Man

Ancient Man

Ancient Man

Ancient Man

Ancient Man